Simulation-first validation for a hardware-heavy system (95% fewer field tests)

We were validating a hardware-dependent drone + sensor system on the drone where meaningful testing required real flights across environments. Each iteration took days, failures were hard to isolate, and regressions were common because validation was gated by field access.

I introduced a simulation-driven workflow built around an interactive Unity-based mission + flight tool. Developers could configure missions on a map (start + target), issue movement/mission commands, and generate synthetic telemetry under configurable RF propagation and antenna orientation assumptions. This shifted validation from rare field events to continuous, developer-owned testing with repeatable baselines for engineering and product decisions.

In practice, the cadence changed dramatically: instead of waiting ~10 days for a flight window (about six field tests over three months), we moved most validation into simulation. Major issues from the previous months were reproduced and fixed in the simulator, and additional problems surfaced within days. Field tests dropped to roughly once every two months and became primarily simulator-to-reality verification. Net effect: 10x+ faster iteration and about 95% less physical testing for comparable scope.

Context

The product was a hardware-heavy system: drones, a sensor package, and a main application (including geolocation logic) on ground control station. Validation depended on real flights, mission configuration, environment-specific RF behavior, antenna orientation and geometry effects, and timing-sensitive interactions between commands and telemetry. In other words, “testing” mostly meant scheduling and hoping conditions lined up.

The problem

The workflow had a built-in bottleneck. The feedback loop was long (meaningful validation every ~10 days), debugging was painful because failures were multi-factor (mission geometry, RF conditions, orientation, timing), and fixes often shipped without fast confidence checks, which increased regression risk. Product and engineering decisions also suffered because there was no stable baseline to compare behavior across changes.

At the root of it, the key inputs were coupled to the physical world and not controllable, and there was no practical way to explore “what happens if we change X?” without flying.

Goal

Enable developers to validate behavior without waiting for field tests by making test conditions configurable, repeatable enough for comparison, fast to iterate, and close enough to reality to be useful.

Solution overview

I introduced an interactive simulation harness that simulates drone flight and mission execution while generating synthetic telemetry as if it came from the real hardware. Developers could configure missions directly on a map (start/target), issue mission and movement commands, and vary the environmental assumptions that mattered most in practice, especially RF propagation and antenna orientation. The simulator fed telemetry into the component under test and captured outputs so behavior could be compared across runs and against baselines.

This effectively created three operating modes: an interactive developer testing loop for fast what-if exploration, regression-style checks using saved configurations and baselines to guard against regressions, and periodic hardware tests used primarily for calibration and simulator-to-reality verification.

Architecture (mapped to diagrams)

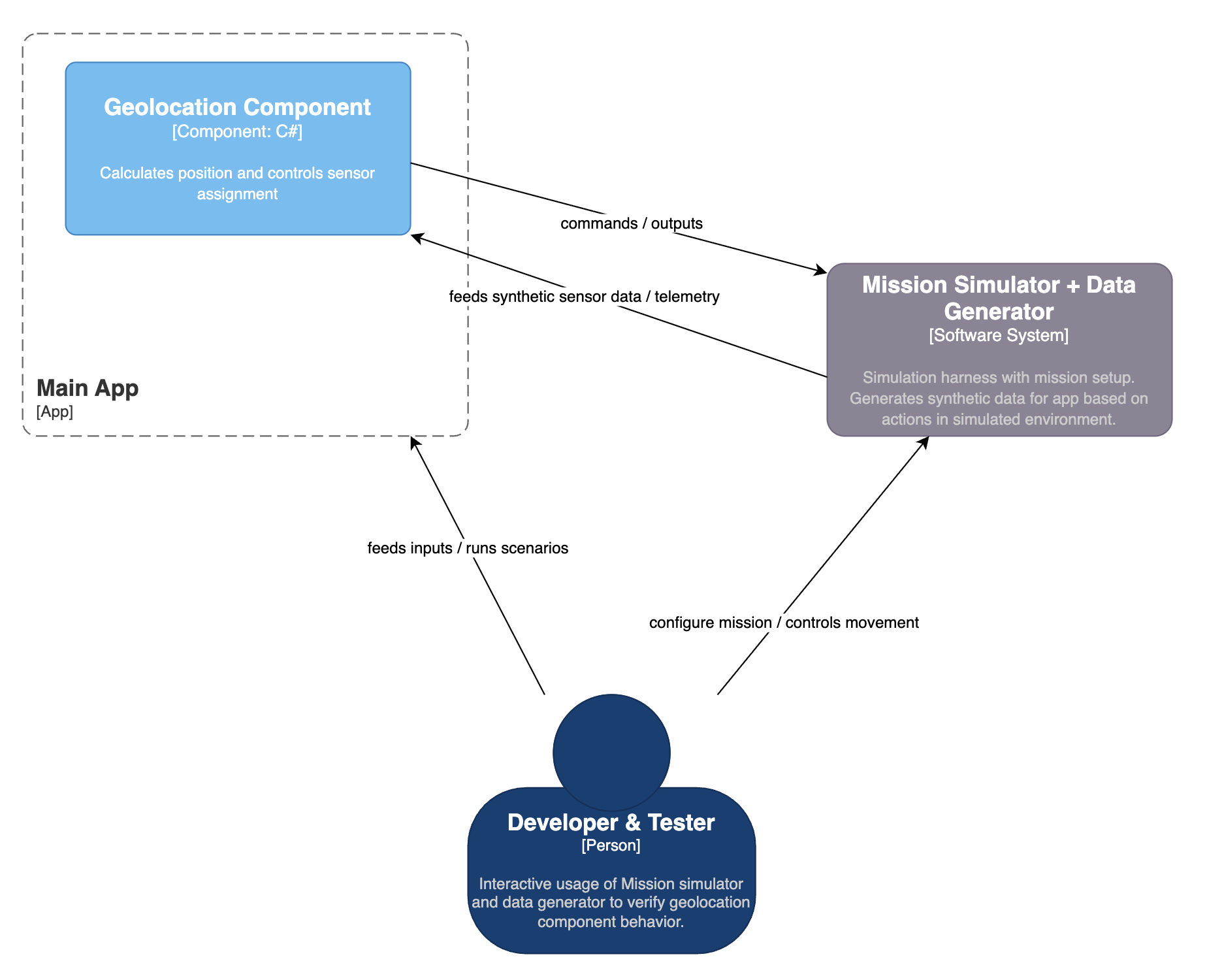

1) Developer interactive simulation loop

The main app consumes synthetic telemetry from the simulator and produces commands/outputs back.

Use case: fast debugging, parameter exploration, isolating root causes.

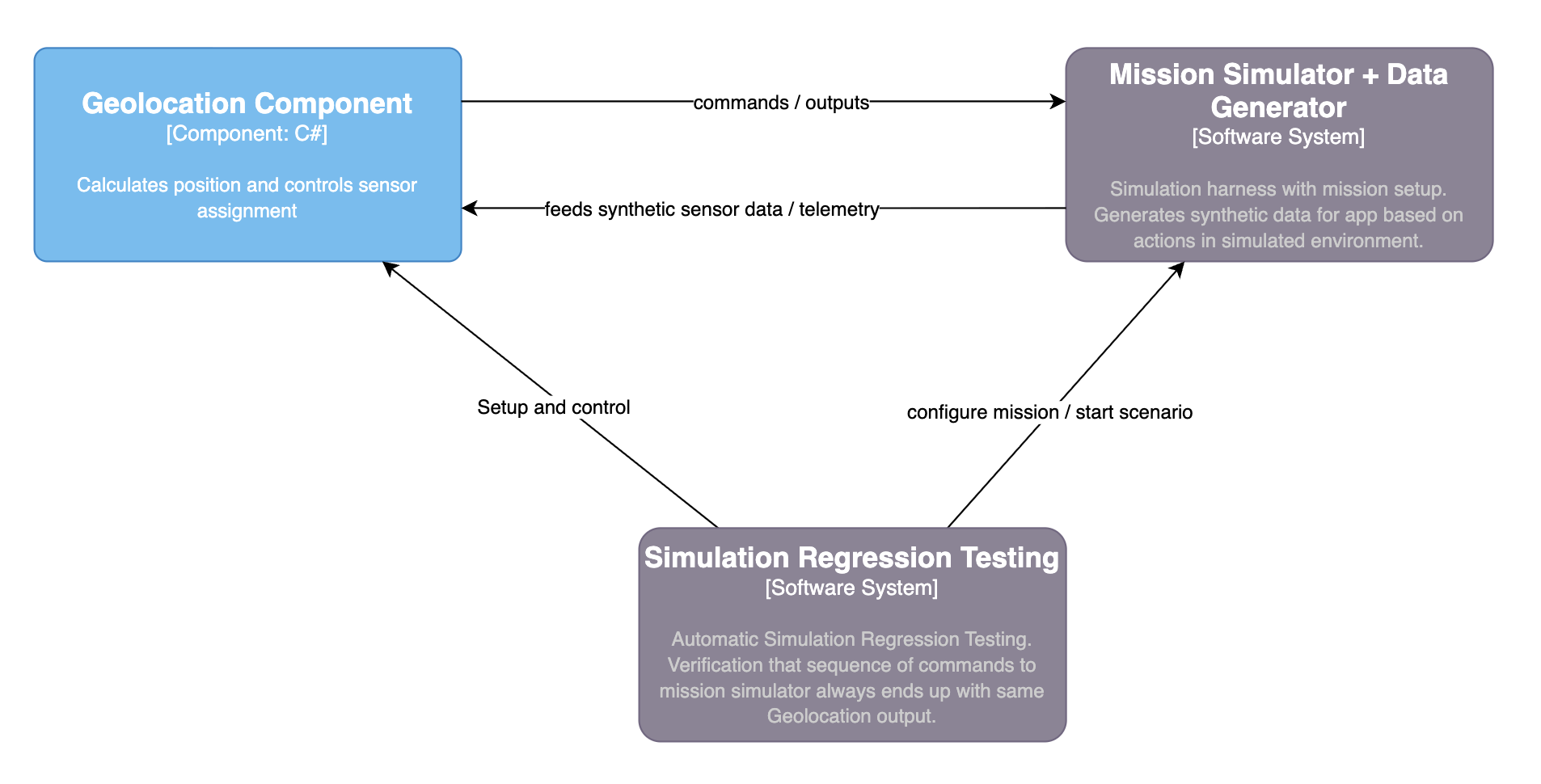

2) Simulation-driven regression checks (optional but high leverage)

A regression layer can run predefined mission configurations (saved start/target + parameters), execute the flow, and verify outputs against baselines.

Use case: catch regressions early and standardize acceptance.

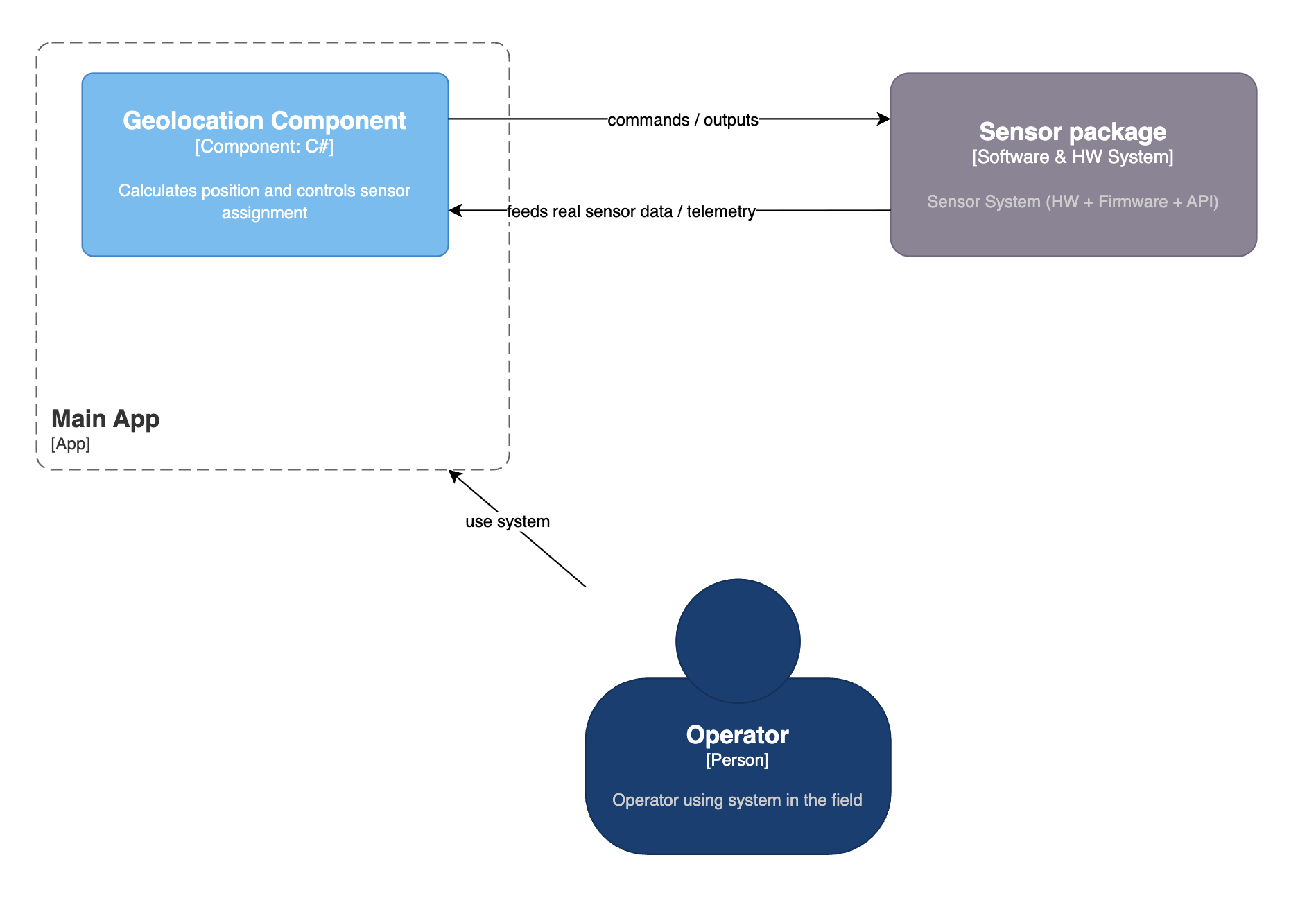

3) Real-world operation (hardware mode)

In production/field mode, the app consumes telemetry from the real sensor package.

What I built: an interactive test tool (not a replay system)

This was not “replay a log.” It was a mission workbench: an interactive simulator where developers could configure a mission, issue commands, and generate synthetic telemetry under realistic constraints that actually matter in the real system.

Mission configuration (map-based)

Missions were configured directly on a map by setting start and target locations. From there, the tool generated flight behavior (paths and movement patterns) driven by the same command logic the real system uses, including realistic timing and transitions such as approach, loiter, and return.

Telemetry generation with pragmatic modeling

The simulator produced synthetic sensor telemetry as a function of the drone’s position over time, target geometry, and the active command sequence. It also included the key real-world effects that dominated behavior in practice, especially RF propagation assumptions and antenna orientation/pointing, with optional noise/latency/drop behaviors to represent degraded conditions. The goal was not perfect physics, but controllable inputs that were “real enough” to expose the same classes of failures.

Interactive “what-if” exploration

Because the inputs were controllable, developers could quickly test questions that were previously expensive to answer in the field, like whether approach angle causes estimate drift, how sensitive the system is to antenna orientation error, how it behaves under degraded RF conditions, and which parameter changes actually trigger a bug.

How it changed day-to-day work

Before

Validation was gated by field access: wait roughly 10 days for a flight window, observe a failure once (often without clean reproduction), argue about the cause, patch something, then wait another 10 days to learn whether it helped.

After

Developers could recreate mission geometry in minutes, vary one factor at a time (orientation, propagation, target geometry, timing), isolate the input regime that triggers failures, and validate fixes immediately. Field tests shifted from “primary debugging method” to periodic simulator-to-reality verification.

Results

Field testing dropped from about 1 per 10 days to about 1 per 2 months, mainly for verification. Iteration moved from days to minutes/hours (10x+ improvement), regressions decreased because validation became continuous and developer-owned, and the overall need for physical testing dropped by roughly 95% for comparable scope (estimated from cadence change).

My role

I identified validation as the main bottleneck on development speed and quality, designed the workflow (interactive mission configuration + synthetic telemetry generation + baseline-driven validation), and drove adoption across engineering and testing so it became routine rather than a side demo. The simulator outputs also provided a shared baseline that supported product decisions with evidence rather than anecdotes.

Details generalized to avoid exposing proprietary internals.

Tradeoffs and risks (reality always wins eventually)

Simulator fidelity vs usefulness

You don’t need perfect physics to unblock development, but you do need honest modeling of the factors that actually drive failures. If the simulator smooths over the real pain points, it becomes a feel-good demo instead of a validation tool.

How we mitigated it: we focused modeling effort on failure-driving parameters (geometry, RF, orientation, timing), validated those assumptions periodically with field data, and treated simulator-to-reality mismatches as calibration work rather than blame.

“Passing simulation” doesn’t guarantee “passing reality”

Simulation can prove consistency and catch regressions, but it can’t certify the physical world behaves nicely. A clean run in a model is not a warranty.

How we mitigated it: field tests remained scheduled verification checkpoints, simulator-to-reality deltas were tracked explicitly, and modeling assumptions were updated as new field evidence accumulated.

Tool maintenance overhead

A simulator is a living system. If it grows into a “mini product,” you end up spending more time maintaining the tool than improving the actual product.

How we mitigated it: we kept the scope narrow (mission + inputs + telemetry relevant to the component under test), made adding/saving configurations low-ceremony, and avoided “pretty simulator syndrome” where visual polish steals time from validation value.

Key takeaways

Hardware-heavy systems need controllable inputs and interactive what-if testing or iteration collapses into waiting. The real win isn’t simulation as a concept, it’s simulation as a daily development tool. Field tests should become verification and calibration, not the only time learning happens.